You feel attached to things you own. And sometimes that can cause big problems (and cost you big time).

If you’ve ever sold a house, you’ve probably entered into a negotiation with the seller. Your asking price is more than they’re willing to pay. You want to realize the biggest gain from the sale. Who doesn’t like the extra cash.

But it’s more than that. At a deep level, that house is worth more to you than to the seller because that house is yours. You’ve lived in it. You’ve painted it. You’ve repaired it. You’ve made memories in it. The seller hasn’t.

You overvalue the house because you own it.

This kind of thing happens all the time:

- A company balks at closing an underperforming branch, even though management would never invest in opening that same branch if it didn’t have it already.

- People who pay $1.28 for a lottery ticket won’t sell the same ticket for less than $5.18, even though with $5.18 you could buy three more tickets and triple your odds of winning.[1]

- Once they owned it, hunters who would pay no more than $31.00 for a hunting license would not resell the same license for less than $138.00.[2]

In each of these cases—selling a house, closing a company branch, selling a lottery ticket, or selling a hunting license—the objective value of the item never changes. The only thing that changes is who’s got it: you or them. And if it’s you, then it’s worth more—based on nothing more than the fact that it’s yours.

The disparity in value is caused by the endowment effect.

What is the endowment effect?

The endowment effect describes the phenomenon where you overvalue things you own, simply because those things are yours.

There are two reasons the endowment effect matters:

- Because the endowment effect causes you to overvalue things you own, you are more likely to accumulate stuff you don’t need and have a hard time parting with it.

- When a marketer makes you feel like an owner, you’re more likely to overvalue it and pay more for what they’re selling.

In this post, we’ll look at the causes behind the endowment effect, the conditions that make you fall for it, and what it means to feel like you own something.

Along the way, you’ll discover a whole bunch of interesting examples of the endowment effect tripping you up. For example, you’ll learn:

- Why test driving a car makes you willing to pay more for it—except when you take a shower right after the test drive.

- Why, when grocery shopping, you should never touch fruits and vegetables, especially avocados.

- Why you’re less likely to return defective products that come with a 30-day money-back guarantee, and more likely to return products without a money-back guarantee.

- Why free trials trick you into liking a product more than you really do.

- Why you’re more likely to purchase products online if shopping from a tablet instead of a desktop computer (and why this works only for physical goods but not abstract items, like experiences).

- Why coupons make you spend more not just by offering a discount, but by changing your perception of value for the product.

- Why you’re less likely to spend money when you get it from a family member instead of a stranger (or from the government in the form of a tax return).

- Why a long shipping period between ordering a product and receiving it makes you less likely to return it.

- Why building or making something yourself just to save money actually can cost more in the end—sometimes a lot more.

- Why you’re more likely to pay too much when you buy a product for the second time.

Is the endowment effect irrational?

Let’s suppose I give you a mug that’s worth $6.00. Then, a few minutes later, someone else offers you $7.00. What do you do? If you’re like most people, you keep the mug, even though with $7.00 you could just buy another mug and still have a dollar left over.

It would irrational to refuse the sale, yet most people do. In a famous experiment, Daniel Kahneman, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard H. Thaler came up with novel way to test at what price points people would willing to buy mugs, and sellers would be willing to sell mugs.[3] They created an artificial market of buyers and sellers. Sellers were given mugs that sold for $6.00 at the campus bookstore–although the experimenters removed the price tag, so participants wouldn’t know the true value. They asked these mug sellers to list the lowest price they’d be willing to sell the mug for. Finally, they asked buyers to list the highest price they would be willing to pay.

What happened?

Most mugs didn’t trade, because most sellers listed prices too high for buyers, and most buyers listed prices too low for sellers. On average, mug sellers would not sell for less than $5.25, while mug buyers would not pay more than between $2.25 and $2.75.

The researchers repeated the experiment with other objects. They started with a pen from the campus bookstore and even left the price tag of $3.98 on the pen. But even with a visible price tag, the same thing happened. Sellers were willing to part with their pens for between $4.25 and $4.75, but buyers, on average, were willing to pay only about half as much.

This makes no sense. Why would sellers who had never had a mug or a pen until that very moment suddenly charge more than the list price? Why would buyers be so cheap? And more importantly: who’s being irrational?

To find out, the researchers created a market with three groups: buyers, sellers, and choosers. Buyers were asked to indicate prices, at 50-center intervals, at which they would buy the mug. Sellers were given mugs and asked to indicate price, at 50-cent intervals, at which they would sell the mug. Choosers weren’t given a mug, but they were asked to indicate at 50-center intervals whether they preferred the mug or cash.

The hypothesis was that choosers would provide the most objective value. As expected, people who had the mug valued it more: $7.12, on average. Buyers valued the mug at $2.87. And choosers valued the mugs at $3.12.

Something about being a mug owner makes you overvalue mugs. That’s not good, especially if you’re trying to sell mugs. Imagine I see you on the street in the morning and ask you at what price you’d prefer a mug instead of cash, and you tell me any price under $3.12 is fine. Now, imagine later that day I give you a mug, no questions asked. It’s yours to keep. A few hours later I offer to buy the mug back, but you won’t sell for less than $7.12. But wait, I say, this morning you told me you’d rather have cash if I offer $3.12? Well yes, but that was before the mug was yours.

See how irrational this is?

But I would never do such a thing, you say.

The truth is that you do. Just hanging on to an object for a while means you don’t want to exchange it.

In another experiment, Jack Knetsch, who was one of the researchers behind the mug study I just described, split people into three groups:[4]

- The first group was given a mug as a thank you for completing a short survey. But before they left the room, they were offered a chocolate bar in exchange for the mug.

- With the second group, he did the opposite: everyone who took the survey got a chocolate bar, and when they exited the room, they got the chance to exchange it for a mug.

- The third group took the survey, but they were given a choice of either a mug or chocolate.

He asked the first and second groups if they wanted to exchange either the chocolate for the mug or the mug for the chocolate, and he asked the first group which gift they wanted: mug or chocolate. He found that when people had mugs, only 11% swapped them for chocolate. And when people had chocolate, only 10% swapped it for a mug. But when people were given an outright choice, 56% chose the mug and 44% chose the chocolate.

What this tells us is that between two items that are nearly equally preferable, people who have one or the other show a strong bias toward keeping that item–just because it’s theirs.

But wait, you say. Why is it surprising that people like what they own?

You’re right. It’s really not too surprising. You don’t need an experiment to tell you that people love their stuff and hate parting with it. You already know that.

So why does any of this matter?

Because you behave irrationally in the way you value your stuff, but you do so in consistent and predictable ways. The endowment effect reveals exactly how this works. When you make a decision, and that decision involves a value assessment, then you need to understand your own inability to judge value accurately. It’s not a big deal when it involves mugs and chocolate. But it is a big deal when it involves big transactions that could cost you.

And it’s an even bigger deal when other people know how the endowment effect works better than you do. Like who? Marketers, salespeople, designers. These are people who attempt to frame your buying decisions in ways that are advantageous to them and disadvantageous to you.

What causes the endowment effect?

The term endowment effect was coined in 1980 by Richard Thaler. He didn’t discover it, but he was the first to systematically study it. Thaler speculated on what causes it, and he came up with a novel explanation.[5]

His explanation had to do with reference points.

Here’s what I mean: If you don’t have an object, then not-having is a reference point. But if you do have an object, then having is my reference point.

This seems obvious and uninteresting until you consider what it means. It means that going from not-having to having is a gain, and going from having to not-having is a loss.

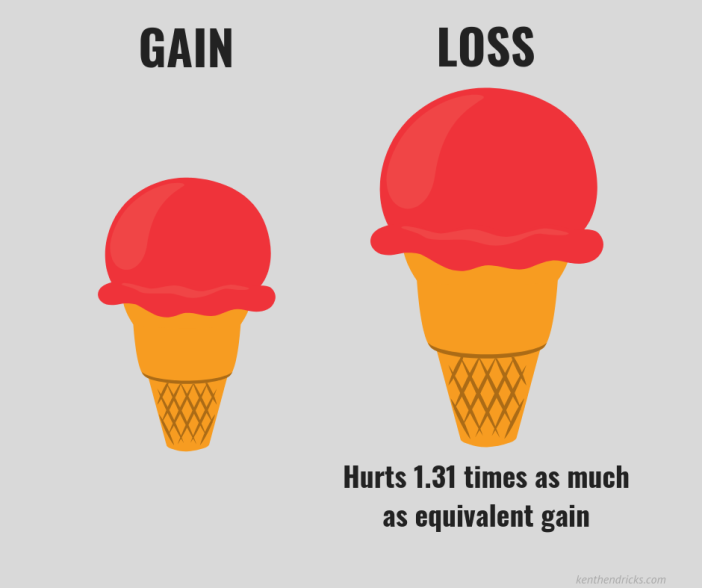

The reason this matters is that losses hurt more than their equivalent gains. Losing $5.00 hurts just a little more than gaining $5.00 feels good. Pretend I offer you a simple coin toss bet. If it lands heads, you get $10. But if it lands tails, then you lose $10. Would you take the bet? Most people wouldn’t. In fact, most people need a $15, $20, or even $25 win to offset the $10 loss if the coin lands tails.

In the late 1970s, right before Thaler was trying to explain the endowment effect, behavioral economists noticed this disparity between losses and gains. They estimated that the ratio of gains to losses was about 2.25-to-1.[6] In other words, you would need a possible gain of $22.50 to offset a possible loss of $10. You value a gain 2.25 times more than its equivalent loss. (Subsequent studies have revised this ratio down to around 1.31. That means on a coin toss bet you would need a win of $13.10 to offset a loss of $10.)[7]

Let’s get back to reference points. When you own something, going from having to not-having is a loss. But if you don’t own something, going from not-having to having is a gain. Even though the objective value of going from having to not-having is the same as going from not-having to having, it doesn’t feel like it. The subjective value depends on which direction you’re going. According to the commonly accepted loss aversion ratio of 1.31, going from having to not-having feels 1.31 times as bad as going from not-having to having.

Your reference point is your starting point, so it matters a great deal. Suppose someone—Thaler calls him Mr. R, so I will, too—buys a case of wine for $5 a bottle. Additionally, Mr. R has never spent more than $35 for a bottle of wine in his entire life.

But Mr. R doesn’t drink the wine. Maybe he’s waiting for the right occasion. Or maybe his tastes have changed.

After a few years ago by, the wine merchant contacts Mr. R and offers to buy the wine back from him at the price of $100 per bottle. That’s a 2,000% return on the $5 he paid for each bottle.

But Mr. R refuses. Why? Because the wine is his.

Now, remember that Mr. R has never spent more than $35 a bottle in his life. That means if he didn’t already own the wine, he wouldn’t buy at the price he is now being offered. If the wine is worth less than $35 a bottle, then Mr. R should keep it. But if the wine is worth more than $5 a bottle, then he should sell it.

Giving up the wine is painful because it’s a loss.

But there’s more going on. Giving up the wine is painful merely because it’s his. He owns it. And as we’ll see, ownership—not loss per se—is the real cause of the endowment effect.

Ownership bias and the endowment effect

If you lose something you own, do you feel the pain because you lost it, or because you owned it? In a clever experiment, Carey Morewedge of Boston University, along with his colleagues, figured out how to separate feelings of ownership from feelings of loss.[8] It took a series of steps to do this. In the first step, they gave people mugs, just like the earlier experiments. In the second step, they asked people to if they wanted to receive either a second mug or money.

They made three assumptions:

- If people had a mug, then they should develop feelings of ownership.

- If ownership causes the endowment effect, then they would overvalue that mug.

- If they overvalued that mug, then they would probably overvalue a second mug just like it.

Notice how people never had to give up their mug. There was no loss—only the possibility of getting a second mug.

So, did people who already have a mug value a second mug more than people who never had a mug to begin with?

Morewedge found that they did. People who had mugs—and who didn’t have to give them up—valued a second mug more than people who had no mugs valued a first mug.

This means the endowment effect is caused by ownership, not loss aversion.

You value what you choose, not choose what you value

Most people assume you first value an object, and then decide to become an owner.

In reality, the opposite happens.

When you choose an object, you create an association between yourself and that object. You come to like objects you associate with yourself, because you like yourself.

But sometimes you don’t like things you choose. Maybe it’s a meal at a restaurant, or a shirt, a new phone, or the house you just bought. (Uh oh.)

Now what?

This mistake creates cognitive dissonance. I like myself. I chose this thing. I don’t like this thing.

At a subconscious level, you try to resolve this dissonance not by liking yourself less, but by liking the object more. Your self-perception anchors your other-stuff-perception.

Researchers at the University of Texas conducted several studies to understand how people form connections with things they own.[9] They started by giving people one of two pictures, and let people pick which one they wanted. It was theirs to keep—a thank you gift for participating in the experiment. The researchers kept the picture each participant selected, and only gave it to them when the experiment was finished.

With the picture selected, people began a set of tasks. The researchers told them they were working on a categorization project; they were supposed to associate a picture with either positive words, like paradise, summer, and harmony, or negative words, like evil, sickness, and vomit. They had to make this association in less than a second.

Because they had so little time, their responses were fast and automatic—formed by gut instinct, not reasoned calculation.

Unbeknownst to the participants, included in the series of pictures was their picture—the picture chose at the beginning of the experiment. It also included the picture they rejected.

Of course, they didn’t know this at a conscious level. One second was not enough time to see a picture, think about whether they had seen that picture before, think about whether the picture they had selected earlier was that picture, or think about the positive or negative words that might go with it.

Yet people were quicker to associate positive words to the picture they selected and negative words to the picture they rejected.

You might object that people liked the picture not because they owned it, but because they actually liked it. After all, they liked it enough at the beginning of the experiment to choose it as the thank you gift. Without thinking back to that choice, presumably they would still like it a few minutes later if they saw it for just an instant as part of a series.

To see, the researchers modified the experiment. They replaced positive and negative words with self- and other-focused words, like me, I, mine, and them, their, they.

But they got the same results. People associate self-focused words to pictures they choose and other-focused words to pictures they reject.

The mere act of choosing is enough to create an association between the person and the object.

What this shows us is that the act of identifying with an object–no matter how small this association is—initiates a kind of ownership.

What’s strange about this is that it’s not real ownership. Money hasn’t changed hands. There’s no receipt.

It’s true that this isn’t ownership in a technical, legal sense. But it is ownership in a different sense.

This is psychological ownership. It’s the idea that there’s no clear break between owning and not owning—that ownership isn’t binary. Instead, psychological ownership lies on a spectrum, and describes degrees of ownership.

Psychological ownership versus actual ownership

Here’s how psychological ownership works.

Compare three scenarios:

- Scenario 1: Let’s say you buy a bicycle, bring it home, and go on a Saturday morning ride with friends. That bike is yours. You own it. There’s a receipt that proves it.

- Scenario 2: But what if you borrow that bike from a friend? You go for the same ride in the morning and return it that afternoon. It’s never technically yours, yet you develop a small attachment to it.

- Scenario 3: What if you’re just dreaming of owning a bike and going on a Saturday morning ride. You’re planning on getting a bike in the future and decide to research your options. You compare models, pick your bike, and select features. But then the worst happens: the bike shop goes out of business. You feel like you’ve lost something. But what? You never exchanged money or even ordered a bike.

This is psychological ownership: you feel ownership by exerting control over an item or object, often by actually owning it. You also feel ownership by merely possessing an item or object, say, by borrowing it. Sometimes, all you need to do is imagine you own a product or anticipate what it might be like to have it.

What would happen if a co-worker left a chocolate bar at your desk without actually giving it to you? How would you feel about the chocolate bar? At what point would the chocolate bar become yours–not theirs? In a study, researchers gave people a chocolate bar but told them they weren’t allowed to eat it.[10] They placed the chocolate bar on their desks, and then spent thirty minutes working on a project—the chocolate ever present, just within reach. At the end of the project, researchers told the people the chocolate bars were now theirs. Then, before they left, people could either keep the chocolate or sell it back. On average, people were willing to sell the chocolate bar for $1.72.

That’s the price of a chocolate bar that’s sat on your desk for a half an hour. Why does this matter? Because in a slightly different experiment, people did the same project without a chocolate bar next to them. Those people valued the chocolate bar at only $1.35 on average.

Remember that neither group believed they were getting a chocolate bar, and neither group technically owned it before the other group. But one group had the chocolate bar in close proximity for a few minutes–on their desk, next to them. This group valued the chocolate bar 27.4% more.

But does this really tell you anything about ownership? Doesn’t it only prove that sitting next to a chocolate bar for a half hour makes you want chocolate? To find out, the experimenters added a third group: actual owners. They were given the chocolate bar at the beginning and told it was theirs.

Here’s what they found. Recall that people who didn’t know about a chocolate bar valued it at $1.35 on average, and people who possessed–but didn’t own–a chocolate bar valued it at $1.72. The experimenters found that people who actually owned the chocolate bar valued it at $1.79 on average.

As you can see, possessing a chocolate bar makes you value it almost as much as actually owning it. Psychological ownership is nearly as powerful as actual ownership. This matters, because when marketers get you to feel like you own something without actually owning it, they can get you to pay more for it.

The causes of psychological ownership

It takes thirty minutes to feel like you own a chocolate bar.

Other studies it takes even less time—sometimes just a few seconds.

Joann Peck from the Wisconsin School of Business and Terry L. Childers from Iowa State University decided to find out how duration of exposure to a product creates feelings of ownership.[11] They worked with a grocery store to make a small change in the way the store displayed fruit by adding a sign above peaches and nectarines that said “Feel the freshness.”

During the period of their study, 239 people bought peaches or nectarines. Half of these people bought the fruit before the researchers hung the sign. The other bought the fruit after seeing the sign. Researchers approached the customers and asked them to fill out a short survey about their shopping experience. They found that, on a scale of 1 to 7, people who didn’t see the sign rated the impulsiveness of their purchase a 3.8, while people who did see the sign rated the impulsiveness of their purchase a 5.4. Seeing the sign made people more likely to pick up the fruit, and picking up the fruit triggered feelings of ownership, which was more likely to lead to an impulse purchase.

Merely touching an object makes you more likely to make an impulsive purchase. But does it also make you value it more? Peck, along with Suzanne Shu from the UCLA Anderson School of Management conducted several follow-up experiments to learn how physical interaction with products changes feelings of ownership and perception of value.[12] They gave participants a mug and a slinky. Half of the participants were allowed to touch the objects; the other half weren’t. The participants were asked to indicate on a scale of 1 to 7 how much they felt the product belonged to them.

Here’s what they found. People who were not allowed to touch objects ranked them a 2.75 on ownership and valued them at $2.73 on average. People who could touch objects and interact with them ranked them a 3.36 on ownership and valued them at $3.38.

The small act of interacting with a product–even for a short amount of time–was enough to activate feelings of ownership and activate the endowment effect.

(The researchers tried the experiment with objects that were unpleasant to the touch, and the feelings of ownership disappeared. It turns out that touching an object only leads to feelings of ownership when that object is fun to touch. Hugging a cactus for a few minutes won’t make you like it more.)

How long does it take to feel a sense of ownership? Pretend you’re having coffee with two of your best friends. You give one of them a mug, and they hold it for ten seconds. You give the other one a mug, and they hold it for thirty seconds. Who values it more? When researchers conducted this experiment, they found that people who held mugs for 10 seconds valued them an average of $2.24 each, and people who held mugs for 30 seconds valued them at $3.07 each. Holding the mug for an extra 20 seconds increased its value by 37%.[13] It takes just a few seconds of touch to make you feel like you own something—and be willing to pay a little more for it.

This effect holds even for digital products. Marketers have found creative ways to simulate psychological ownership, even when you can’t touch the products you’re about to buy or examine them in person. One recent study found that presenting a three-dimensional image that consumers could rotate with their mouse increased feelings of ownership by 18.9% compared to a flat, 2D image. On a 7-point scale meant to indicate perceived ownership, people who saw two dimensional, flat images ranked products at 3.58, compared to 4.26 from people who saw three dimensional images they could rotate with their mouse.[14] Making product images vivid and interactive produces greater psychological ownership, which causes a higher perceived value–and makes you more willing to pay for it.

Even the experience of shopping online using a tablet instead of a desktop computer makes you feel more like an owner while you browse products. When you use a tablet, you must hold it in your hands and interact with it using your fingers to touch and swipe. But when you shop on a desktop computer, you sit a little further way and use a mouse. You interact with your tablet in a more physical way, which also makes you more likely to buy physical goods than were you to browse on your desktop computer.

This effect only holds for physical goods. It doesn’t work for abstract goods. For example, while shopping on your tablet makes you more likely to buy a soft, warm sweatshirt, it doesn’t make you any more likely to buy something abstract, like a tour of New York City.[15]

Quasi-ownership

We’ve now seen how physical association with products make you feel a sense of psychological ownership. But physical association isn’t the only way to create psychological ownership. There are other ways you feel ownership. We’ll call this quasi-ownership.

Auctions make you value a product more

You have probably experienced quasi-ownership at an auction, or at least you’ve seen it in others. One of the reasons for this is that auctions make you feel like you own the items you bid on—even before the bidding closes. You feel more ownership when more time has elapsed between your first bid and your final bid.

Researchers discovered that when people bid on DVDs on eBay, they increase their bids by $4.00 on average each time they bid—except on the last day, when they the increase jumps to $5.00.[16] But why? Because people who had been bidding on a DVD since bidding opened were more willing to increase their bids as they got closer to the end. This held true across over 115,325 auctions that were examined. When you bid on items, your feelings of ownership grow a little each day—each time you check your item, each time you raise your bid. You feel like you own the item you’re bidding on long before it’s yours.

The earlier you begin bidding, the more you feel like you own the item. And the later you begin bidding, the less you feel like you own the item. In an experiment, researchers held an auction with nine bidding rounds. Half of the participants were allowed to bid in every round, while the other half had to wait until the last round to place their first bid. Both groups had all the same access to information: which items were up for auction, what the bids were, and how many rounds were left. The only difference was that one group could bid while the other group sat and watched until the final round.

As expected, the first group developed feelings of ownership throughout the first eight rounds. By the ninth and final round, they bid $6.39 on average.

The second group, however, who had not been allowed to bid, bid $4.02 on average in the final round—$2.37 less than the first group.

Why the difference?

Because, for the first group, the endowment effect kicked in at the very beginning. And with each successive round, the items became more valuable.

But for the second group—the group who couldn’t bid until the very end—felt no sense of ownership. For them, the endowment effect didn’t kick in until the last round. Why place a high bid on an item that doesn’t feel quite as much yours?

Coupons make you value a product more

Much like auctions, coupons cause feelings of quasi-ownership, too.

You’re more likely to buy something with a coupon, because the coupon narrows the gap between the price of the product and the price you’re willing to pay. It does this by bringing the price down.

Coupons close the gap in another important way. They not only bring the price down, but they also bring the amount you’re willing to pay up.

Coupons do this by making you feel a sense of ownership. In a study, people were given coupons to restaurants with comparable prices and levels of service. At the end of the experiment, people were given the opportunity to either keep their coupon or sell it. Researchers found that having a coupon increased the value from $6.30 to $10.20.[17]

Thinking about a product makes you value it more

Even thinking about a product can be enough to make you value it more. Researchers asked people to rank music albums they wished they owned. When they were able to get people to elaborate on what they found appealing about an album, they were able to get them to pay more.[18] Another study found when people were given a high-end address book, they valued it more highly after they wrote a story about how they might use it.[19]

You’re willing to pay almost as much for a product after you just think about the product as you would after you actually use it. Remember the study about slinkies I mentioned earlier—how playing with a slinky makes you willing to pay more for it? That same study found when people imagined themselves using the slinky they were willing to pay $3.59, compared to $3.38 for people who actually played with it.[20] (People who neither played with nor imagined playing with the slinky were willing to pay only $2.73.)

When you imagine yourself using a product, you trigger an endowment effect almost as powerful as one produced from actually owning and using the same product. This is why marketers craft ads that make it easy to imagine using a product. You’re the one smelling the towels after using the laundry detergent, you’re the one drinking the Corona on the beach, and you’re the one with the happy family at Disneyland.

Here’s a clever ad from Capital One for a credit card that provides a small percentage of cash back on certain purchases. It’s hard to sell a credit card with such an abstract benefit. Instead, they sell you the card by helping you imagine the experiences you can have with the card. And the experiences they show are physical and tangible. You can probably imagine yourself doing these things:

- Escaping a rainstorm by entering a dry building

- Spilling wine on your date’s sweater—on your first date, no less

- Singing karaoke

- Eating ramen with chopsticks

- Kissing your date at a basketball game—and having it appear on the big screen

By making those experiences salient—and by linking their credit card to those experiences—you’re much more likely to take the action they want you to take.

Length of ownership and the endowment effect

You also assign greater value to items you’ve owned for a long time compared to items you’ve owned for a short time. Michael Strahilevitz of the University of Miami School of Business, along with George Loewenstein of Carnegie Mellon University, conducted an experiment in Israel to find out how duration-of-ownership affects the way people value products.[21] They gave people a keychain. For half of the people, the researchers offered to buy it back a few minutes later. For the other half, they waited a whole hour. They found that people who kept the key chain for a few minutes sold it back for 4.10 shekels, on average. But as people held it longer, they demanded higher prices. After an hour, people wanted 5.31 shekels, on average.

In another version of the experiment they gave mugs to three groups of people. For the first group, they offered to buy the mug back right away; this group valued the mug at $2.69. After a minute, the value rose to $3.95. And after an hour, people wouldn’t sell it back for less than $4.97, on average.

It wasn’t just value that increased over time. People’s perceptions of how others valued the mugs changed, too. The longer people possessed the item, the more likely they were to think their peers would prefer their item to a different item. The endowment effect made it harder to discern the objective value of their item.

There are a couple of interesting applications of the duration-of-ownership effect. Let’s say you purchase a coloring book on Amazon. In the process of researching various coloring books, adding (and removing, and adding them back) to your cart, previewing pages, and rotating 3D images, you’re increasing your sense of ownership–along with the price you’re willing to pay.

Next, you make the transaction and become the legal, actual owner of your brand-new coloring book.

But it doesn’t stop there. Your coloring books are on their way, but you don’t have them just yet. In the time it takes to receive the shipment, your anticipation builds, and your sense of ownership increases.

A few days later, your coloring books arrive. As you open the package and begin using the coloring book, your feelings of ownership increase even more. It’s more yours than it was on the day you bought it, and even more yours than it was on the day you started using it.

Then, one day, you notice an error on one of the pages of the coloring book. Had you known about this error, you never would have bought it in the first place. Yet here you are, with a defective coloring book.

What do you do? Do you return it?

If you’re like most people, you keep it. It’s not worth the hassle of calling Amazon or shipping it back.

Why not? Because you’ve developed strong feelings of ownership, beginning with your research process, growing through the waiting period, and growing still more as you used your product. Had you discovered the error the day you received it, you would have been more likely to return it.

Many stores offer a window of time when you can return the product, no questions asked. You’ve probably seen these messages: “Satisfaction guaranteed or your money back!” Stores do this for three reasons:

- They know a money-back guarantee makes a transaction more likely.

- They know most people wait until the end of the period they’re allowed to return a product to actually do so.

- They know people are less likely to return a defective product when they’ve owned it longer.

The longer you own a product, the more you value it. And the more you value it, the less likely you are to return it.

You value products differently depending on where they come from

Imagine you’re in the market for a new bookshelf, and there are three possible ways to get it.

- Your friend from work is moving and offers to give you his—he even offers to deliver it to your house that evening. Your new bookshelf is a complete surprise.

- You built your own bookshelf by hand. Maybe you like working with wood or maybe you just want to save a little money by making it yourself. You selected the wood and built it in your shop or your garage.

- A dear friend has died, and you’re going through the things they left behind. To your surprise, they have left you their one and only bookshelf.

Which bookshelf is worth more?

Pause and reflect: a bookshelf doesn’t care where it came from, or who built it, or how you got it. In fact, in the truest (and perhaps crudest) sense, it’s irrational to value an object like a bookshelf differently depending where it came from. Each scenario ends with you getting the same bookshelf.

Yet the way you acquire each bookshelf is very different: in the first instance, by surprise; in the second, through hard work; and in the third, from someone special. To you, these bookshelves are worth different amounts: the first is worth the least, the second is worth a little more, and the third is worth the most.

Why does an object’s source determine its value more than an object’s own properties, like the quality of the wood?

Because you endow objects differently depending on where you get them from.

How you value items you get as a result of random chance

There are endless ways to stumble into ownership without planning to. Think of the things you get through what seems like random chance: maybe it’s a great deal on something from Craigslist or Facebook. Maybe it’s an unexpected check—a tax return, an inheritance check. Maybe it’s a job opportunity, a deal on a house, or the Amazon customer service rep telling you to keep the item they’ve just refunded. All of these acquisitions are delightful surprises–which, unfortunately, you don’t value quite as much as you should.

How does receiving a product by surprise change how you value it? George Loewenstein and Samuel Issacharoff tested this by giving their students a quiz. They rigged it, so every student got an A or an A-. Next, they gave all their students a mug. The catch was that half of the students were told they got the mug because they did well on the quiz, and the other half were told they got the mug through a random selection process. The only difference between the two groups was that one believed they earned the mug by performing well, and the other thought they got the mug by sheer luck.

How did the two groups value their mugs? People who believed they got the mugs as a result of random chance valued them at $5.25 on average. People who believed they earned the mugs with good grades valued them at $6.75 on average.[22]

When you get something by chance, you don’t value it as highly as if you’ve earned it.

The IKEA effect: you value items more when you make them yourself

The IKEA effect describes your tendency to overvalue things you make yourself. It’s named after the furniture store which famously requires that customers build their own furniture. IKEA provides some basic tools, some nuts and bolts, and a set of instructions, but it’s up to you to put it all together.

The act of making something yourself causes it to value it more. You hang on to that piece of IKEA furniture a little longer than the already-built furniture. You admire the pottery you paint yourself a little more. You think the food you made yourself tastes a little better.

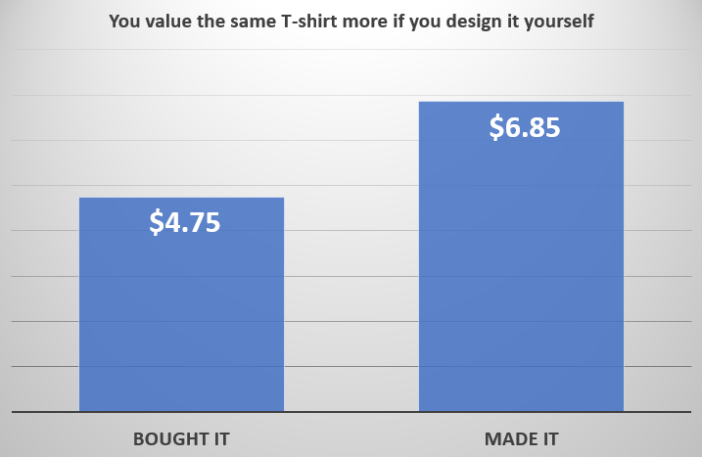

But by how much? Nikolaus Franke and his colleagues decided to find out how much more people valued items when they helped make them. They asked people to bid on t-shirts. Half of the people selected t-shirts off a shelf, to simulate the experience of buying a shirt in a store. The other half bid on a t-shirt they had designed according to a specific set of instructions.

What this second group didn’t know was that the t-shirt they designed was identical to the t-shirt on the shelf. Yet the group who thought they had created their own, unique shirt was willing to pay much more—$6.85 on average, compared to $4.75 for people who didn’t participate in designing the shirt. Remember, the t-shirts were identical.[23]

Even stronger experimental evidence comes from people who participated in an experiment that mimicked furniture assembly. People who assembled a small box were willing to pay $0.78 for it, while those who didn’t assemble the box would only pay $0.48. When you build a box yourself, it’s worth 63% more to you. People who built boxes also liked them more–3.81 on a scale of 1 to 7, compared to 2.5 for people who didn’t build the box.[24]

The same is true for works of art. When the researchers showed people how to make origami, those who learned how to make small frogs and cranes themselves valued their creations at $0.25, on average. In fact, they valued their own creations only slightly less than the origami created by experienced experts ($0.27).

But maybe people realize they’re overvaluing their own creations. Deep down, they know their own origami doesn’t compare to the experts’ origami. To test this, the experimenters went back to those origami creators and asked them to guess how much others, not they themselves, would value their creations. The average guess was $0.19. But people who didn’t make the origami were asked what the origami creations were worth, they guessed only $0.05 each—they “saw the amateurish creations as nearly worthless crumpled paper.”

The truth is, by participating in the creation process, you become incapable of assessing an object’s true value. Strangely, though, the IKEA effect can compensate for deficiencies you may have in other domains. For example, if you’re unable to solve a math problem, you’ll be more willing to assemble a piece of IKEA furniture than someone who solves the math problem successfully.[25] It’s as if, after failing in one area, you know you can get a quick win—thanks to the endowment effect—by building some Nordic furniture.

The endowment effect is stronger when you get an object from someone you love

Items you get from close family and friends are “priceless,” you often say. You place a high value on these items—but just how much?

In an experiment, 183 people were given various objects and asked to assign an objective value to them, along with a price they were willing to pay.[26] People gave wildly different values to the same items, depending on their relationship to the person they got the items from:

- When the objects came from a close family member, or from someone with whom that person shared a close emotional bond, people assigned a value of $30, but were willing to pay $300.

- When objects came from an employer, a coach, or someone who had authority over them, people assigned a value of $12, and were willing to pay $45.

- When objects came from a casual friend, co-worker, or classmate, people assigned a value of $11 and were willing to pay $40.

- When objects came from a clerk, a customer, or someone else who had a purely transactional relationship with that person, people assigned a value of $30 and were willing to pay $50.

What if, instead of getting an object, you get cash?

Keep in mind that a check for $75 doesn’t change in value depending on whether you got it from your grandmother, your best friend, your boss, or a kind stranger. The source is irrelevant.

Yet when people receive an unexpected gift of $75 from a close relative, 60% of recipients don’t spend it. When the money comes from a co-worker, only 47% of people save it. And when people get the money from a stranger, only 34% of people save it.

When you receive a cash gift from someone close to you, it has more value, and you’re less likely to spend it.

The endowment effect depends on whether the transaction happens in the present or the future

You might not realize it, but you make decisions today on behalf of your future self all the time. It’s worth asking: is the endowment effect greater for transactions that happen in the present than in the future?

This might seem like a silly question. After all, you can’t have a transaction in the future, because as soon as the future arrives, it’s the present. You can’t travel in time.

Yet your future self is stuck with the decisions your present self makes. You’re constantly guessing how your future self will value things, and you’re making financial decisions today based on those assumptions.

Let’s go back to the mug experiments: half of the group gets an item and becomes sellers; the other half gets no item and becomes buyers. The act of ownership causes sellers to endow it with more value than buyers and demand a higher price.

These two examples get at the same question: what is your present self willing to pay for something in the future? Dong Woo Ko from the University of Iowa decided to test this experimentally.[27] He asked people: “If you could buy the pen through an online site today, how much would you pay for it? You don’t need to consider shipping fee.” People who were buying the pen–owners–endowed the pen with less value than sellers. Already having a pen makes you value it more. This is the result you’d expect.

But then he asked a slightly different question: “If you could buy the pen through an online site three months from today, how much would you pay for it? You don’t need to consider shipping fee.”

Did you catch the difference? The first question asked people about the present; the second asked people about the future. What would you pay three months from now? instead of What would you pay today?

When people were asked to make the transaction the same day, buyers were less willing to buy, and sellers were less willing to sell. That’s because buyers, having not felt ownership of a pen, valued it less.

But when asked about whether they would make the same transaction in the future, things changed. Buyers were willing to pay a higher price, and sellers were willing to sell for less.

This is the opposite of what you would expect. If you’re selling a pen three months from now, you’ll have an extra three months to develop feelings of ownership. It would seem these feelings of ownership should cause you to value the pen more, not less, causing you to charge a higher price.

What this experiment shows is you’re unable to predict how your future self will value objects. Your present self cannot predict how your future self will think, feel, or behave, so you make decisions today you think your future self will be fine with. But when the future arrives, your present self is stuck with the bad decisions your past self made.

It’s as if your future self is a completely different person–a person you don’t know quite as well as your present self. Yet your present self is in the awkward position of making important decisions whose outcomes your future self has no choice but to accept.

Think about your stuff. What would be hard to part with?

Fast forward ten years. Is it still as hard?

Let’s use real estate as an example. It’s easier to imagine your ten-years-from-now self selling your house instead of your present self selling your house, even though it will be harder for your ten-years-from-now self, since the endowment effect will be that much stronger.

Your present self needs to avoid decisions that will constrain your future self. It might be harder to imagine your future self parting with an object than your present self. But it will be just as hard–and probably harder–for your future self than your present self.

How to avoid falling for the endowment effect

Bad news: the endowment effect is basically unavoidable. Fortunately, there are a few ways you can escape some of its worst effects.

Repeat experience

Some initial studies indicate it might be possible to overcome the endowment effect with practice. Three scholars looked at several experiments on the endowment effect, and found that when the experiment is repeated, buyers are willing to pay a little more, and sellers are willing to accept a little less. The endowment effect doesn’t disappear altogether, but it isn’t quite as strong.[28]

In another experiment, researchers found that people who participated in five trades in a row saw a marked decrease in the endowment effect by the fifth trade.[29] Practice doesn’t make perfect, but it does help.[30]

When trades are easy to make goods in abundant supply, people know that if they make a bad trade, there’s always next time. for everyday items that are easy to buy, sell, and replace, you’ll experience less of an endowment effect than, say, for your house. There’s only one house that’s yours. Sure, you can get a new house, but it’s not yours.[31]

Wash your hands

One of the best ways to temper the endowment effect is to wash your hands. If that sounds absurd, consider this. Behavioral scientists have shown a strong connection between handwashing and moral behavior. People who wash their hands are less judgmental. An experiment found that when people who watched video clips of others committing morally and physically disgusting acts, they responded with judgment—as you would expect—unless they washed their hands.[32] Washing your hands also makes you less likely to feel the need to justify your past decisions,[33] and it makes you less likely to believe there’s a connection between a past success and the success of a future risky option.[34]

What these and other studies point to is that handwashing sets a cognitive reset button. It not only cleans you in a physical way, but it also demarcates “before” from “after” in your mental processing.

Handwashing sets a reset button on the endowment effect, too. In an experiment, researchers gave people a soft drink before distracting them with a series of tasks.[35] At the end of the experiment, subjects were given the opportunity to exchange their drink. Only 23.1% of the subjects were willing to exchange, thanks to the endowment effect. But in another version of the experiment, they made people wash their hands before giving them the option to exchange their drink. When people washed their hands, 52.8% of people exchanged the soft drink–a significantly higher number than the 21.1% of people who didn’t wash their hands. The simple act of handwashing seemed to mitigate the endowment effect, making their soft drink easier to part with.

Next time you need to make a big financial decision, such as buying a car or a house, give yourself enough time between evaluating the car or the house and making the transaction. In the intervening time, go home, rest, relax, take a shower, and reconsider your options. It really will help.

Move to a tribe of hunter-gatherers

As pervasive as the endowment effect is, it appears it’s largely a product of market economies. In fact, the evidence points to a complete absence of the endowment effect in hunter-gatherer societies. Researchers visited one of the last hunter-gatherer peoples on the planet, the Hazda tribe in Tanzania. The Hazda is comprised of tribes that have varying exposure to market economies, primarily in the form of tourists on a safari. The researchers found that the more exposure a tribe had to a market economy, the more likely they were to endow items they received with additional value. In the tribe with the least exposure to a market economy, the researchers detected virtually no endowment effect. Tribe members who were given objects seemed not to give them extra value, and they had no trouble trading those objects with other tribe members.[36]

Tips for avoiding the endowment effect

It’s in the best interest of marketers, salespeople, and product designers to get you to overvalue things, because when you do so, you’ll pay more. And you’ll be less willing to part with what you’ve got. The tendency is powerful–but, as we’ve seen, it’s also irrational.

Perhaps the best way to prevent the endowment effect from causing you to overvalue items is to avoid situations where marketers, salespeople, and retailers want you to feel a sense of ownership. Avoid free trials, auctions, and product tests. Resist salespeople who try to get you to imagine using a product. In most cases, it costs less to pay more for something than to build it yourself. Be aware of how you treat the stuff you get depending on who it’s from.

You can’t avoid falling for the endowment effect altogether. It’s impossible to escape natural behavioral tendencies. But by being aware–and by being smarter than those trying to manipulate you–you can take steps to bring your subjective value of your stuff into closer alignment with its true, objective value.

Want more content like this?

Roughly once per month I’ll send you a new article just like this one. You’ll learn how to make better decisions, understand your customers, and grow your revenue.

Who subscribes? CEOs, professors, marketers, designers, salespeople, non-profit leaders, and investors. Join them by signing up right now.

“I highly recommend subscribing to Kent Hendricks’s newsletter. Imagine if The Atlantic and Wait But Why had a child, who grew up to become an esteemed psychology researcher / game theorist. That’s kind of what reading his work is like.”

—Jeffrey Kranz, Co-founder/CEO, Overthink Group

[1] Knetsch, J. & Sinden, J. (1984). “Willingness to pay the compensation demanded: Experimental evidence of an unexpected disparity in measures of value.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 99(3), 507-521.

[2] Heberlein, T. and Bishop, R. (1985). “Assessing the validity of contingent valuation: Three field experiments.” Science of the Total Environment 56(15), 99-107.

[3] Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J., and Thaler, R. (1990). “Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem,” Journal of Political Economy 98(6) 1325-1348.

[4] Knetsch, Jack L. (1989). “The Endowment Effect and Evidence of Nonreversible Indifference Curves.” American Economic Review 79, 1277-84.

[5] Thaler, R. (1980). “Toward a positive theory of consumer choice.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 1, 39–60.

[6] Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D. (1992). “Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty.” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 5(4), 297–323.

[7] Walasek, L., Mullett, T., and Stewart, N. (2018). “A meta-analysis of loss aversion in risky contexts.” SSRN.

[8] Morewedge, C.K., Shu, L., Gilbert, D., and Wilson, T. (2009). “Bad riddance or good rubbish? Ownership and not loss aversion causes the endowment effect.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 45(4), 947-951.

[9] Gawronski, B., Bodenhausen, G., and Becker, A. (2007). “I like it, because I like myself: Associative self-anchoring and post-decisional change of implicit evaluations.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43(2), 221-232.

[10] Reb, J. and T. Connolly (2007). “Possession, feelings of ownership and the endowment effect.” Judgment and Decision Making 2, 29–36.

[11] Peck, J. and Childers, J. (2006), “If I touch it I have to have it: Individual and environment influences on impulse purchasing.” Journal of Business Research 59(6), 765-769.

[12] Peck, J. and Shu, S.B. (2009). “The effect of mere touch on perceived ownership.” Journal of Consumer Research 36(3), 434–447.

[13] Wolf, J., Arkes, H. and Muhanna, W. (2008). “The power of touch: An examination of the effect of duration of physical contact on the valuation of objects.” Judgment and Decision Making 3(6), 476–482.

[14] De Vries, R., Jager, G., Tijssen, I., and Zandstra, E. H. (2018). “Shopping for products in a virtual world: Why haptics and visuals are equally important in shaping consumer perceptions and attitudes.” Food Quality and Preference, 66, 64–75.

[15] Adam Brasel, S and Gips, James. (2013). “Tablets, touchscreens, and Touchpads: How Varying Touch Interfaces Trigger Psychological Ownership and Endowment.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 24(2), 226–233.

[16] Heyman, J., Orhun, Y., and Ariely, D. (2004). “Auction fever: The effect of opponents and quasi-endowment on product valuations.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 18(4), 7-21.

[17] Sen, Sankar and Johnson, E. (1997., “Mere-Possession effects without possession in consumer choice,” Journal of Consumer Research 24, 105–117.

[18] Carmon, Z., Wertenbroch, K., and Zeelenberg, M. (2003). “Option attachment: When deliberating makes choosing feel like losing.” Journal of Consumer Research, 30(1), 15-29.

[19] Lewis, E. (1997). “Kung Fu address books: The relationship between pricing and narrative.” Working paper.

[20] Peck, J. and Shu, S.B. (2009). “The effect of mere touch on perceived ownership.” Journal of Consumer Research 36(3), 434–447.

[21] Strahilevitz A. M., and Loewenstein G. (1998). “The effect of ownership history on the valuation of objects.” Journal of Consumer Research 25, 276–289.

[22] Loewenstein, G. and Issacharoff, S. (1994). “Source dependence in the valuation of objects.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 7, 157-168.

[23] Franke, N., Schreier, M., and Kaiser, U. (2010). “The ‘I designed it myself’ effect in mass customization.” Management Science 56(1), 125-140.

[24] Norton, M., Mochon, D. and Ariely, D. (2011). “The IKEA effect: When labor leads to love.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 22(3), 453–460.

[25] Mochen, D., Norton, M., and Ariely, D. (2012). “Bolstering and restoring feelings of competence via the IKEA effect.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 29(4):363-369

[26] McGraw, A.P., Tetlock, P. and Kristel, O. (2003). “The limits of fungibility: Relational schemata and the value of things.” Journal of Consumer Research 30(2), 219-229

[27] Ko, D., Hedgcock, W., and Cole, C. (2011). “Temporal distance and the endowment effect,” in Advances in Consumer Research 39. Eds. Rohini Ahluwalia, Tanya L. Chartrand, and Rebecca K. Ratner, Duluth, MN: Association for Consumer Research.

[28] Knez, P., V. Smith, and Williams, A. (1985). “Individual rationality, market rationality, and value estimation.” American Economic Review 75(2), 397-402.

[29] Shogren, J., R. Wilhelmi, C. Koo, S. Cho, C. Park, and P. Polo (1996). “Auction institution and the measurement of WTP and WTA.” Unpublished manuscript, 1996.

[30] List, J. (2003). “Does market experience eliminate market anomalies?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(1), 41–71.

[31] Horowitz, J. K., and McConnell, K. E. (2002). “A review of WTA/WTP studies.” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 44, 426–447.

[32] Schnall, S., Benton, J., and Harvey, S. (2008). “With a clean conscience: Cleanliness reduces the severity of moral judgments.” Psychological Science 19(12), 1219–1222.

[33] Lee, S.W.S. and Schwarz, B. (2010). “Dirty hands and dirty mouths: Embodiment of the moral-purity metaphor is specific to the motor modality involved in moral transgression.” Psychological Science 21(10), 1423–1425.

[34] Xu, A., Zwick, J., and Schwarz, N. (2012). “Washing away your (good or bad) luck: Physical cleansing affects risk-taking behavior.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 141(1), 26-30.

[35] Florack, A., Kleber, J., Busch, R., and Stöhr, D. (2014). “Detaching the ties of ownership: the effects of hand washing on the exchange of endowed products.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 24(2), 284-289.

[36] Apicella, C., Azevedo, E., Christakis, N. and Fowler, J. (2014). “Evolutionary origins of the endowment effect: Evidence from hunter-gatherers.” American Economic Review, 104 (6): 1793-1805.